Exosomes in Sports Medicine: Recovery, Responsibility, and the Boundaries of Ethical Performance

Understanding the Role of Exosomes in Sports Medicine

By Op. Dr. Hilmi Karadeniz

A Personal Starting Point from an Orthopedic Surgeon and Sports Medicine Physician

A sports medicine perspective on recovery without doping

I am Op. Dr. Hilmi Karadeniz, an orthopedic surgeon who has worked with athletes for many years now. Some of them were competing at a very high level, others were not well known at all. What they had in common was not fame or income. It was dependence. Dependence on a body that had to function reliably, often under pressure, often without much margin for error.

Early in my career, I believed what many young physicians believe: if you diagnose correctly, treat properly, and follow the textbook, recovery will take care of itself. Over time, that belief faded. Not because it was wrong, but because it was incomplete.

What I began to see, especially in competitive sport, was that healing and recovery rarely follow clean timelines. Injuries do not always resolve when we expect them to. Pain disappears, but function does not fully return. Imaging looks acceptable, but the athlete does not feel stable. Something is “off,” even if no test can clearly show it.

This is usually the moment when the most dangerous decisions are made. Not dramatic ones. Small ones. Returning a bit too early. Increasing load just a bit too fast. Ignoring a warning sign because the season schedule leaves little room for patience.

Most careers are not destroyed by a single wrong decision. They erode slowly.

Performance problems are often recovery problems

When athletes tell me that they feel they are “losing performance,” I rarely hear about strength or motivation. What I hear instead are descriptions that are harder to quantify.

A sprinter talks about a hamstring that never feels quite right anymore. A football player describes a knee that tolerates training but reacts badly to match intensity. A tennis player explains that the shoulder pain is gone, but the confidence is not. These are not excuses. They are observations.

In many cases, the underlying issue is not capacity, but recovery. Tissue that has healed just enough to function, but not enough to tolerate repeated high load. Inflammation that is no longer acute, but never truly resolved. Neuromuscular control that has adapted around an injury instead of being restored.

Modern sport does not fail athletes because they train too little. It fails them because recovery does not always keep up with demand.

That realization has changed the way many of us think about performance. Not as something to be pushed endlessly, but as something that has to be protected.

What exosomes in sports medicine actually are – without the hype

Exosomes are small extracellular vesicles that every human body produces naturally. They are not synthetic, not artificial, and not foreign to our biology. Their primary role is communication.

Cells use exosomes to exchange information. They transport microRNAs, proteins, lipids, and other signaling molecules that influence how surrounding cells respond to stress, injury, or inflammation. This process happens constantly, whether we are injured or not.

What matters medically is not that exosomes exist, but what they do. They help coordinate repair. They influence inflammatory balance. They participate in how tissues adapt after damage.

What they do not do is force outcomes. Exosomes do not stimulate muscle growth. They do not increase oxygen transport. They do not override physiology. They work quietly, in the background, influencing conditions rather than commanding results.

This subtlety is exactly why they are interesting. And also why they are often misunderstood.

Why athletes became interested in Exosomes in Sports Medicine

Athletes are not, in my experience, searching for shortcuts. They are searching for reliability. They want to know whether their body will hold up tomorrow, next week, next season.

The situations in which exosomes are discussed are usually very specific. Chronic tendon problems that do not respond to rest or physiotherapy. Cartilage stress that limits training volume. Post-surgical recovery where strength returns faster than tissue quality. Repeated overload injuries without a clear structural cause.

Pain medication can reduce symptoms. Cortisone can calm inflammation temporarily. But neither improves tissue resilience in the long term. And simply “training through it” often makes things worse.

Exosomes entered the conversation because they act at a different level. Not symptom suppression, but modulation of the biological repair environment. That does not mean they solve everything. It means they may support healing when the body struggles to organize it on its own.

Exosomes in Sports Medicine: A necessary clarification – this is not performance enhancement

This point deserves clarity, especially in sport.

Exosomes do not make athletes faster, stronger, or more enduring in a direct sense. They do not raise VO₂ max. They do not increase muscle mass. They do not replace training or discipline.

When performance improves after appropriate regenerative treatment, it is usually because something that was limiting performance has been removed. Pain, instability, chronic inflammation. The athlete is not exceeding their natural capacity. They are returning to it.

That difference matters. Medically and ethically.

Recovery is not enhancement. Restoration is not manipulation. Confusing the two leads to poor decisions and unnecessary fear.

Where medicine has to be careful

Every medical tool can be misused. Exosomes are no exception.

In a legitimate medical context, their use is considered only when there is a clear diagnosis, a documented indication, and a structured rehabilitation plan. The goal is to restore tissue quality so that normal function becomes possible again.

Problems arise when biological approaches are used without medical necessity. To suppress pain. To shorten recovery beyond physiological limits. To maintain performance under overload instead of addressing it.

At that point, the intention changes. And intention matters.

Medicine exists to protect athletes, not to help them ignore their bodies. The difference between support and manipulation is not always dramatic, but it is always important.

Recovery and return to play are biological processes

One of the most common mistakes in sports medicine is equating pain reduction with readiness. Pain is only one signal. It is not the whole picture.

True return to play requires more than symptom relief. Tissue integrity has to be restored. Neuromuscular coordination has to be rebuilt. Load tolerance has to be tested gradually. Adaptation takes time, even when pain is gone.

This is why modern sports medicine increasingly relies on integrated approaches. Orthopedic assessment, physiotherapy, movement analysis, load management, and sometimes regenerative support. None of these elements work well in isolation.

Exosomes, when used, are part of this process. They are not a shortcut. They do not replace rehabilitation. They only make sense when embedded in a structured medical plan.

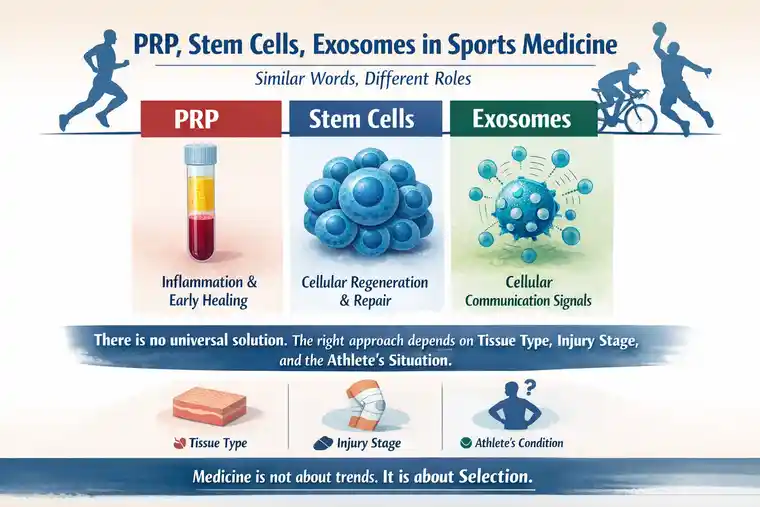

PRP, stem cells, exosomes in sports medicine – similar words, different roles

These terms are often used interchangeably in public discussion, but medically they serve different purposes.

PRP primarily influences inflammation and early healing responses. Stem cell–based therapies provide cellular support in regenerative contexts. Exosomes act as messengers, coordinating communication between cells.

There is no universal solution. The right approach depends on tissue type, injury stage, and the athlete’s overall situation. Choosing the wrong tool at the wrong time rarely helps.

Medicine is not about trends. It is about selection.

Quality and oversight in Exosomes in sports medicine matter more than the method

One aspect that is rarely discussed publicly is variability. Not all exosome preparations are equal. Source material, isolation methods, purification standards, and handling all influence biological behavior.

From a medical perspective, this is not a minor detail. Poor quality control introduces unpredictability. And unpredictability is the enemy of responsible medicine.

Athletes often focus on outcomes. Physicians have to focus on process. Transparency, documentation, and oversight are not obstacles. They are safeguards.

Ethics in sport are not abstract

Sport depends on trust. Between athletes and physicians. Between teams and the public. Between performance and integrity.

Innovation in medicine will always move faster than regulation. That is not a problem in itself. It becomes a problem when responsibility does not keep pace.

Exosomes force us to ask questions that are uncomfortable but necessary. Are we restoring health or chasing marginal gains? Are we listening to biological limits or trying to silence them? Are medical decisions driven by diagnosis or by pressure?

These questions do not have simple answers. But ignoring them is never the right choice.

What I want athletes to understand regarding Exosomes in Sports Medicine

Exosomes are real biological messengers. They have legitimate medical applications. They are not magical solutions, and they are not shortcuts.

Recovery is not the enemy of performance. It is its foundation.

When regenerative approaches are used responsibly, they do not push athletes beyond their limits. They help them return to where they belong.

Closing thoughts about Exosomes in Sports Medicine

Modern sports medicine is not about creating superhuman performance. It is about preserving the human body under extraordinary demands.

Exosome-based therapies do not promise miracles. They do not replace training, patience, or discipline. What they may offer, when used correctly, is the chance for proper healing.

And when healing is respected, performance follows naturally. Not as an artificial boost, but as the result of a body that has been allowed to recover.

That is not doping.

That is medicine doing what it is supposed to do.

Medical responsibility, ethical clarity, and long-term athlete welfare must always come first.

FAQ’s regarding Exosomes in Sports Medicine

Are exosomes banned in professional sports?

This is where things often get misunderstood.

Right now, exosomes are not specifically named on most anti-doping prohibition lists. That’s true. But that alone doesn’t make them automatically acceptable.

In sport, it’s never just about whether something appears on a list. What really matters is how it’s used, why it’s used, and what it does to the athlete’s body. If a substance or method is applied without a genuine medical reason, or if it’s clearly being used to gain an unfair advantage in recovery or performance, it can still become a problem – even if it hasn’t been formally banned yet.

This is why relying on technical gaps is risky. In anti-doping, history has shown many times that rules tend to follow biological reality, not the other way around.

So the short answer is: not explicitly banned does not mean approved – and it certainly doesn’t mean safe from consequences.

Can exosomes actually improve athletic performance?

Exosomes do not make athletes faster, stronger, or more powerful in a direct way.

What they may do – in medically justified cases – is support recovery by calming inflammation or supporting tissue repair. When inflammation or injury has been limiting performance, this support can feel like an improvement.

But that is very different from artificially enhancing performance.

Exosomes do not replace training, conditioning, or discipline – and they do not create abilities the body does not already have.

Are exosomes detectable in anti-doping tests?

There is currently no routine test designed to directly identify externally administered exosomes during doping controls.

That said, modern anti-doping systems do not rely only on finding substances. They also look at biological patterns over time. Unusual recovery speeds, atypical biomarker changes, or deviations in an athlete’s biological passport can still raise questions – even without a single identifiable compound.

So while exosomes may not be “visible” in a traditional sense, their effects may not be invisible at all.

Are exosomes in sports medicine safe for athletes?

Safety depends entirely on how, why, and from where they are used.

Exosomes prepared under proper medical standards, for clear clinical reasons, are normally well tolerated with no or just very light side effects within the first 24 – 48 hours after the treatment.

What often gets overlooked is that we simply don’t have decades of experience with this – especially not in healthy, high-performance athletes. Most of the data we have comes from medical contexts, not from people pushing their bodies week after week at the limit.

The bigger problem, though, is not the science itself. It’s the way exosomes are sometimes offered. Different sources, different preparation methods, very different levels of quality control. When treatments move outside proper medical supervision, the risks stop being theoretical.

In professional sport, even a small medical issue can spiral. A missed competition. A failed check. A question you suddenly have to explain. Careers have been derailed by far less.

Will anti-doping regulations change in the future?

If you’ve been around professional sport long enough, you’ve seen this story before.

New medical or biological tools appear, they sit in a gray zone for a while, and people argue about whether they really matter. Then research advances, real-world use increases, and eventually the rules catch up.

That’s usually how it goes.

Athletes who make decisions based purely on what isn’t written down yet often underestimate how quickly that window can close. Anti-doping authorities don’t wait for trends – they respond to patterns, outcomes, and risk.

From a medical point of view, it’s far safer to assume that regulations will evolve than to assume that today’s silence will last. That is why transparency and caution matter far more than trends.

Get your free consultation

- Need guidance and reassurance?

- Talk to a real person from MedClinics!

- Let's find the perfect doctor together.